Following an eventful birth in 1985, the infant Cyclone Comics was in for more change in 1986. Gary Chaloner, creator and co-founder, added publisher to his list of credits when McKerr Whitfield (according to Chaloner’s recollection in the preface) “went bust”. This change added financial responsibility to the mix but – as we will see – had no other significant effect on the product.

With each issue of Cyclone Comics, the young creators felt a growing confidence in their product. Almost inevitably, the closeness of the group resulted in their respective characters crossing over into each other’s tales. Chaloner was simultaneously learning about the history of Australian comics, thanks mostly to John Ryan’s 1979 book Panel By Panel: An Illustrated History of Australian Comics. This education would have an effect on the makeup of his stories.

Cyclone Redux: The Adventures of Flash Damingo & The Jackaroo #2 continues the action of the premiere issue, reprinting stories from Cyclone! Australia #3 & #4. Not surprisingly, the cliff-hanger from the previous issue is quickly resolved and the action continues.

Absent for the entire first issue, headline character The Jackaroo now takes sole possession of the story title and appears throughout – beginning by striking a heroic pose in the opening splash. By the end of the second page, he meets Harry Pattison, a police sergeant he briefly encountered in issue 1 and – finally – Flash Damingo, the wise-cracking, diminutive platypus-alien with the Italianesque accent. During their introductions, we learn that The Jackaroo is hunting The Barnacle as a suspect in the death of the Jackaroo’s friend, Margaret Bourne. But all is not as it seems.

This all takes place in the sewers under the headquarters of O.G.R.E, the evil organisation infiltrated in the previous issue. Inside O.G.R.E, a surprising development unfolds. Without revealing the exact nature of the twist, we find Lieutenant James Clive-Kirby under interrogation. He rapidly reveals that Flash is on Earth purely to enlist help against the Zotian Empire. Having served his purpose, he is quickly and ruthlessly dealt with. Within this scene, Chaloner introduces two characters of note: Lieutenant Smith of The Southern Squadron making a crossover appearance in this title, and a mysterious alien who will feature later in the story.

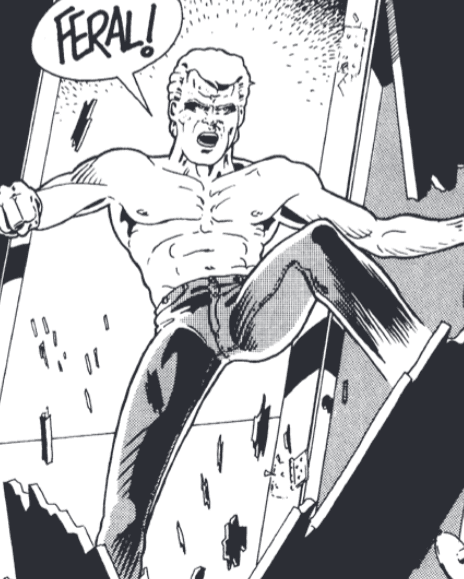

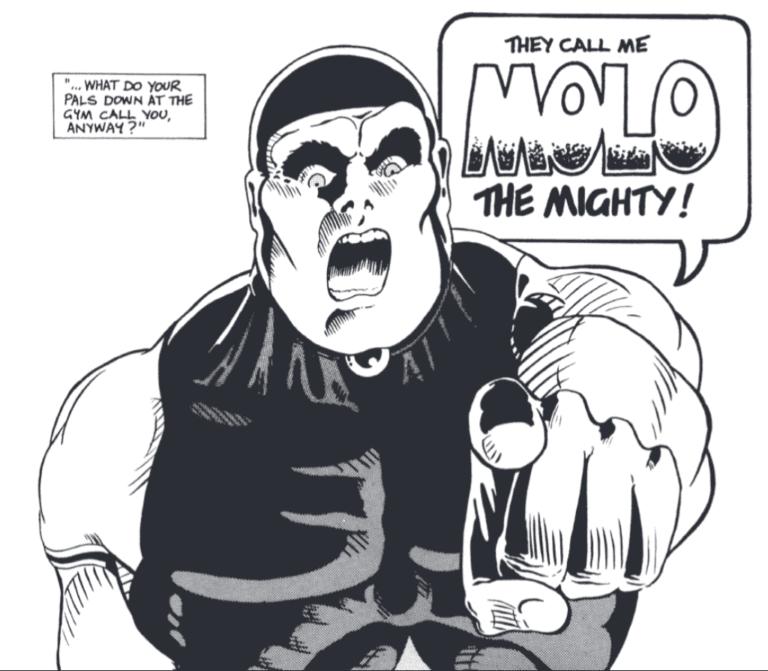

We rejoin some supporting cast from the first issue: Doc Surly, Theodore Marley and ‘Monkey’ Rench, as they make a rather gruesome discovery. Meanwhile in the sewers, Harry brings The Jackaroo up to speed on recent events. Flash disappears down a tunnel, seemingly on a private mission of his own, just before Harry and The Jackaroo are attacked by the unnamed alien. He reveals himself as Molo the Mighty, a confirmed homage to an obscure 1950s Australian comic book character. A lengthy battle ensues, during which The Jackaroo learns the true fates of Margaret Bourne, Smith and Clive-Kirby. Also revealed are the secret roles of Molo and The Barnacle, as well as the fearful Feral. She reveals herself to be a Zotian princess, chasing the renegade Molo in search of a mystical headband in his possession. With this headband, Feral expects to gain the power to seize control of her planet, from her father’s hands.

If you think that is a lot of characters to track and learn, cue the entrance of Nightfighter, another member of the Southern Squadron. Several battles ensue with varying outcomes, followed by the return of Flash and a final confrontation with Feral. After defeating the rabbit assassin first seen in the previous issue, The Jackaroo holds his own against Feral until Molo arrives, settling his differences with the alien princess in a rather dramatic manner. With the Zotian incursion resolved, all that remains is to count the casualties on both sides and clean up the mess. Everything is as it should be with no loose ends – or is it?

Five chapters later, I feel the visual dynamics and narratives reflect a growing internal confidence in Chaloner, as he develops the elements of his universe. At times, the action slows because of what seems to be needlessly wordy ‘catch-up’ exposition. However, when allowed to, Chaloner’s innovative layouts and increasingly polished art dictate the flow of the story as they should. Dialogue at times seems to be trying a bit hard to create an Aussie ‘ocker’ feel. The attempt should be applauded, and I expect that the style will settle into something distinctly and credibly Australian. The beginnings of a shared universe are a welcome aspect of this issue and I hope that this will grow over the remaining seven issues in this series.