Australia, early to mid 80s: something was happening. After twenty years, our comics were beginning to come back.

It’s not my place as a reviewer to delve into the details or the reasons for this. Amid all the American superheroes and mutants in our newsagents and the scattered emergence of new comic shops, buyers began to see books with Australian characters, Australian locales and uniquely Australian voices (cultural cringe notwithstanding).

One such book was ‘Adventure Illustrated’, the brainchild of Gary Chaloner. This book was produced as a promotional issue and as proof-of-concept. Sadly, Sydney rain and a leaky warehouse ruined all but a few copies. Undaunted, the creative team tried again, and within weeks ‘Cyclone’ was born. Many will know the characters and creators featured in this first issue: ‘The Dark Nebula’ by Tad Pietrzykowsy (pencilled by Glenn Lumsden); ‘The Southern Squadron’ by Dave de Vries; ‘Golden Age Southern Cross’ by Tad and Glenn.

Gary Chaloner provided the series that would eventually be known as ‘Flash Damingo and The Jackaroo’.

Cyclone Redux: The Adventures of Flash Damingo & The Jackaroo (2017) ran for nine issues. The purpose of this series was to present the original stories to new and old readers. As Gary foreshadows in the final issue, it also paves the way for new adventures to come.

The first issue spends a lot of time introducing us to the characters, which is to be expected. In the opening story, we meet ‘The Jackaroo’: already involved in a chase, seeking to stop an apparent arch-rival: ‘The Barnacle’. They are joined by two policemen, who provide a combination of backing characters, dramatic foils and comic relief (thanks to the interplay between the long-suffering sergeant and the very green rookie). The action in this self-contained story serves mainly to introduce all four characters.

This issue goes on to tell the main story in three chapters. It is not until the beginning of this story that we meet our second title character: ‘Flash Damingo’. We meet a rabbit assassin from the planet Zot. In apparent tribute to the mania surrounding them at the time of writing, several members of the Sydney Swans AFL team make a training session cameo. Chapter One deals with an attempt on Flash’s life, thwarted in a rather unusual manner.

Chapter Two brings Flash together with the police introduced in the first story, as he enlists them in his quest. We are then introduced – in fairly quick succession – to a second Zotian assassin (who doesn’t stick around long); the bike riding Doctor Clarke Surly, “saviour of the world, fighter of crime, all-round good guy and American citizen”; and lieutenant James Clive-Kirby. The latter is very English in tone and clichéd in habit but appears to be a member of Flash’s entourage, even arriving on a crashed spaceship.

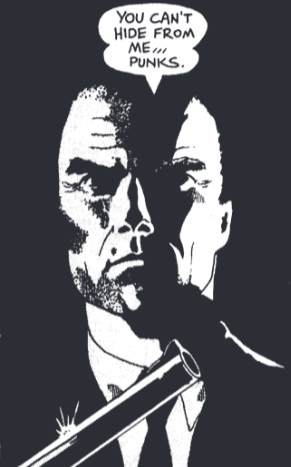

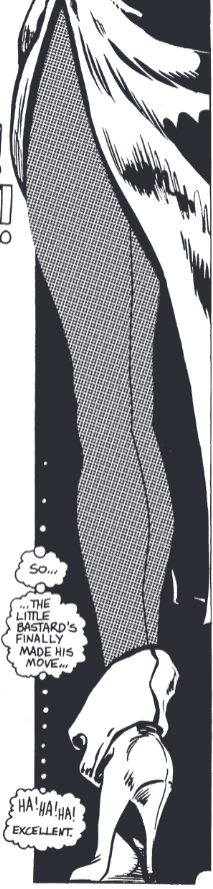

In Chapter Three, we meet the final two members of the cast – two aides to Doctor Surly. The reason for Flash’s arrival on Earth is revealed and the action gets underway for real. The Barnacle reappears and we learn two things about him. Firstly, he works for a woman depicted only by a shadowed face and shapely, stockinged leg. Secondly, he looks and sounds a lot like Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry, a very popular cinematic character at the time.

After several pages of action, a little character description, and revelation of powers and abilities, we reach a cliff hanger ending. Will our heroes survive? Grab the next exciting issue!

The Jackaroo is notably absent from the 3-part story, which is odd as this book includes his name in the title. Perhaps we will learn why in future chapters.

By Chaloner’s own admission, these first stories suffer somewhat from crude art, bad jokes and questionable characterisation. But for all that, the attempt to bring a story with a largely Australian feel and sense of place succeeds (somewhat). It will be interesting to see if both art and dialogue improved as the creator gained more confidence in his story and the characters. Page breakdowns and panel layouts are the strongest of the technical aspects and both facial expressions and action shots tell the story required. Improvements in line work can only improve on this. The dialogue and exposition at times seem overly wordy, as if in response to a need to compress the space required to tell the story.

As a first chapter and a debut artistic outing, this book has both much to commend and much to improve upon. This reviewer will be sticking around to see if the potential is realised.